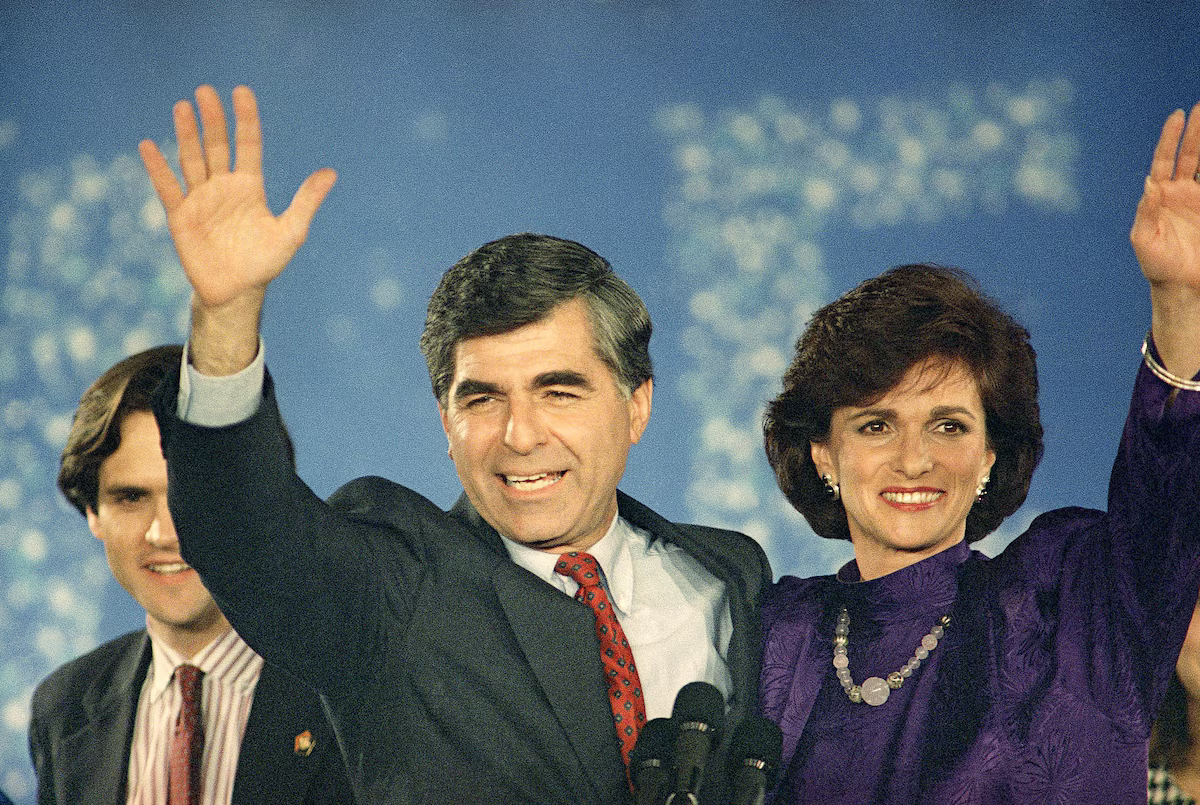

Kitty Dukakis, Humanitarian and Activist for Mental Health, Dies at 88

She campaigned fiercely for her husband, Michael Dukakis, in the 1988 presidential election, spoke openly about her struggles with addiction and later promoted electroconvulsive therapy as a treatment for depression.

The Washington Post

Updated March 22, 2025

By Glenn Rifkin

Kitty Dukakis, who was the wife of former Massachusetts governor and 1988 Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis and who publicly battled addiction and became a prominent advocate for electroconvulsive therapy as a treatment for depression, died March 21 at her home in Brookline, Massachusetts. She was 88.

The cause was complications from dementia, said her son John.

As her husband governed Massachusetts (from 1975 to 1979 and again from 1983 to 1991) and ran for president, Mrs. Dukakis carved a distinct identity in public life. She was a modern-dance instructor, a social worker, an arts patron and an activist on behalf of vulnerable populations, from the homeless to the stateless.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, she took part in the resettlement of Vietnamese, Laotian and Afghan refugees, using her status and political access to navigate the bureaucratic morass.

On a humanitarian trip to the Thai-Cambodian border in 1985, she fell to her knees before a Thai colonel, begging for entry into an off-limits refugee camp. “I think he was so thunderstruck by my doing that and knew I wasn’t going to get off my knees until he said ‘yes,’ ” she later told the Boston Globe.

When the colonel relented, Mrs. Dukakis located a Cambodian orphan, a survivor of Khmer Rouge rule, whose only surviving relative lived near Boston. She brought him to Massachusetts, where he graduated from high school and attended college.

As first lady of Massachusetts, Mrs. Dukakis described herself as driven by “compassion and humanitarian concern.” She said she was “fiercely proud” of her Jewish background — her husband was Greek Orthodox — and played a role in the creation of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.

Her intense personality, chain smoking and preference for first-class travel and designer clothes both complemented and provided a contrast to her husband’s straight-arrow persona. Calm, button-down and abstemious, he nursed a frugality that extended to flying coach and mowing his own lawn as governor. (Massachusetts does not have an official residence for its governor.)

“Michael can take a peanut out of the can,” she once remarked. “I eat the whole can.”

Mrs. Dukakis fielded criticism that she was overbearing and impolitic in her dealings with state officials who she felt were inattentive to her causes or insufficiently deferential to her husband. She ascribed such criticism of her to jealousy and sexism.

“Have you ever heard the words assertive or aggressive used to describe the male spouse of a candidate?” she asked the Los Angeles Times. “I think there’s a real double standard when it comes to strong, assertive women.”

A tough campaign

She campaigned fiercely for her husband, and never harder than during his losing presidential bid against then-Vice President George H.W. Bush. As a potential first lady, she endured a great deal of media scrutiny, and she spoke openly about overcoming a crippling 26-year amphetamine dependency that started when she began abusing diet pills at 19.

“I would have done it had Michael been a candidate for president or not,” she told Reuters, explaining her motivation for her disclosures. “One of the tenets of recovery is helping others. I knew I would have an even greater opportunity to help others in a national campaign.”

The frenzy of a campaign played to many of Mrs. Dukakis’s strengths and seemed to energize her. But she also battled depression and, by her own account, became expert in hiding her alcohol dependency as the stresses of the presidential bid mounted.

As Dukakis played up the Bay State’s economic boom — the “Massachusetts Miracle” — Republicans depicted him as ultraliberal, unpatriotic and soft on crime.

His veto of a 1977 Pledge of Allegiance mandate for public schools was used to question his patriotism. His soundness on crime was attacked in a commercial that spotlighted a weekend prison furlough granted to a convicted murderer who, after failing to return to prison, raped a Maryland woman and stabbed and pistol-whipped her fiancé. The prisoner, Willie Horton, was Black, and the commercial was widely denounced as appealing to racial prejudice.

Dukakis’s dispassionate resolve, verging on an apparent lack of emotion, also cost him with voters.

During the final presidential debate, CNN moderator Bernard Shaw asked Dukakis, “Governor, if Kitty Dukakis was raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?”

Dukakis’s response — ignoring the hypothetical attack on his wife and reiterating his opposition to the death penalty — helped seal his defeat at the polls. Mrs. Dukakis later said she was infuriated by the question, calling it “outrageous.”

Bush won an electoral-vote landslide, 426 to 111, with a margin of eight points in the popular vote. Dukakis returned to work at the State House, commuting by subway as usual, and struggling to keep the Massachusetts Miracle alive amid a rising state deficit and his plunging approval ratings.

Mrs. Dukakis had a far more turbulent return from the campaign trail. She would see her husband off to work in the morning and then retreat to her bedroom to drink. At times, she recalled, she disguised herself with a kerchief, dark glasses and a fake mole drawn on a cheek before going out to buy vodka that she would hide in a laundry hamper. Sometimes she passed out in her own vomit, to be discovered by her husband or children.

She was hospitalized for alcoholism in February 1989. That November, on the first anniversary of her husband’s defeat, she drank rubbing alcohol and nearly died. She insisted that she had been seeking relief for insomnia, but media reports cast the incident as a possible suicide attempt. “The only certainty,” Washington Post columnist Mary McGrory wrote, “is that she wanted the world to know how unhappy she is.”

The next year, Mrs. Dukakis published “Now You Know,” a memoir written with Jane Scovell and detailing Mrs. Dukakis’s contentious relationship with her mother, her life as a political spouse and her addictions. She was widely praised for her forthrightness about her struggles. They continued through the next decade as she cycled in and out of drug-treatment centers and psychiatric facilities, while somehow completing a master’s degree in social work at Boston University in 1996.

She tried antidepressants and treatments that included talk therapy, but nothing helped. In her memoir, she recounted that she continued to binge drink whatever was available: vanilla extract, mouthwash, aftershave and even nail-polish remover.

In desperation, she turned in 2001 to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The method, formerly called shock therapy, had long been held in the popular imagination to be barbaric, a conception reinforced by the Oscar-winning 1975 film “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” which is set in a mental institution. In one graphic scene, Jack Nicholson’s character is held down and sent into seizures by electric shock.

Mrs. Dukakis’s doctor reassured her that the procedure, in its modern form, was a safe, comfortable and effective way to treat severe depression.

She had her first treatment the morning of June 20, 2001, the Dukakises’ 38th wedding anniversary, and awoke, she said, feeling immediate relief. As the former governor was driving her back to their Brookline home, Mrs. Dukakis, in a stunning shift in her demeanor, said, “Let’s go out to dinner tonight!”

For Mrs. Dukakis, the shock treatments worked so quickly and so well that she called them a “miracle in our lives.” With journalist and author Larry Tye, she wrote the 2006 book “Shock: The Healing Power of Electroconvulsive Therapy.” In speeches and interviews, Mrs. Dukakis noted that temporary memory deficits were associated with the treatment and that she required regular maintenance sessions. But she and her husband became vigorous proponents for ECT.

“Kitty Dukakis was the most prominent person in the world to ever stand up and say, ‘ECT worked for me, and we ought to look at what the health and science implications of it are,’” Tye said. “She managed to take every one of her infirmities and every one of the incredible trials in her life and figure out a way that other people could benefit from them.”

Not a mommy’s girl

Katharine Virginia Dickson was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Dec. 26, 1936. She was nicknamed Kitty, after her mother’s close friend, actress Kitty Carlisle Hart.

Her father, Harry Ellis Dickson, the son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants, was the first chair violinist for the Boston Symphony Orchestra for nearly 50 years. He was also a popular associate conductor of the Boston Pops, filling in regularly for Arthur Fiedler.

In her autobiography, Mrs. Dukakis wrote: “No question, I am a daddy’s girl.” With her mother, the former Jane Goldberg, the dynamic was different.

“There was often friction,” Mrs. Dukakis wrote. She found her mother abrasive, demanding and withholding of praise. She remembered that her mother picked her up at the airport once — she was returning from Penn State — and chided her for wearing jeans and sneakers, adding, “Kitty, you are getting fatter and fatter.”

She quit college at 20 to marry a classmate, John Chaffetz, and accompanied him to California for his Air Force assignment. They had a son, John Jr., but divorced soon after.

Starting over, she enrolled at Lesley College (now Lesley University) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to study for a bachelor’s degree. She was also raising a toddler as a single mother when a mutual friend set her up on a date with Michael Dukakis — then a young lawyer on the cusp of entering the Massachusetts state legislature.

His parents were opposed to his marrying someone from outside the Greek Orthodox faith, not to mention a divorcée with a child. But the two were wed in 1963. Mrs. Dukakis’s parents, on the other hand, were delighted that she had found someone so unflappable and promising. “Jane, my wife, used to call him Jesus Christ,” Harry Ellis Dickson told the Los Angeles Times.

Michael Dukakis adopted his stepson, who took his surname, and the couple had two daughters, Kara and Andrea. In addition to her husband and children, survivors include seven grandchildren.

Mrs. Dukakis received a bachelor’s degree from Lesley College in 1963 and taught modern dance while encouraging her husband’s political ambitions. She suffered three miscarriages, lost a baby shortly after birth and had major surgery for two herniated disks that might have left her paralyzed. “I’m a very strong woman,” she said to the Chicago Tribune in 1988, six years after she received a master’s degree in broadcasting and film from Boston University.

In the later decades of their lives, the Dukakises remained mostly out of public life but were active in promoting ECT. In a 2017 NPR interview, the couple shared their feelings about its impact.

“I certainly feel that I have had a new lease on life, and I feel very fortunate and full of gratitude for that,” Mrs. Dukakis said.

Her husband added, “I don’t have to tell you that the difference is just dramatic. And the fact that she’s now in a position to encourage literally thousands and thousands of others to try the same thing is a great thing to be able to do.”

Category: